by Cayla Iske, PhD | Nutritionist, Oxbow Animal Health

Muesli and seed-based mixes have been popular choices for pet parents for decades. In this four-part series, we’re taking a closer, research-based look at the truth behind commonly held beliefs and claims regarding popular mixes.

Missed an installment of the series? Catch up on previous installments before reading on!

True or False: There is no evidence that mixes are bad for my small pet.

FALSE: As we’ve shown in our evaluation of previous claims about mixes throughout this series, there is an abundance of documented research that has proven that mixes aren’t healthy for rabbits, guinea pigs, and many other small exotic species.

To build on this existing research and take a more in-depth look at the composition and nutritional profiles of commonly available muesli and foraging mixes on the market, we decided to develop and complete our own nutritional evaluation of these products.

A Look at Our Nutritional Evaluation Process

Three top-selling muesli/foraging mixes were selected and methodically sorted into individual ingredients which were each analyzed for nutritional composition.

- This process allowed us to determine specific percentages of individual ingredient makeup in each bag.

- Furthermore, we referenced and utilized published selective feeding consumption data to calculate what animals would likely be consuming compared to the composition of what is in the bag.5

What’s In The Bag? Nutritional Component Breakdown

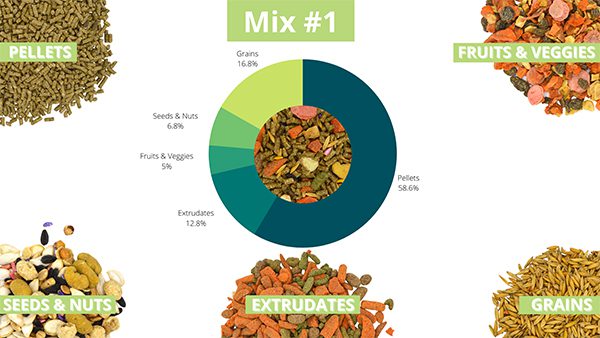

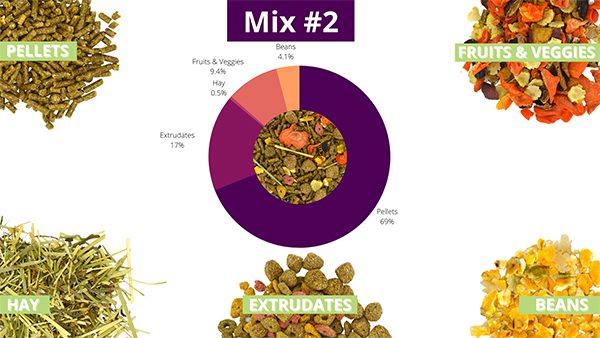

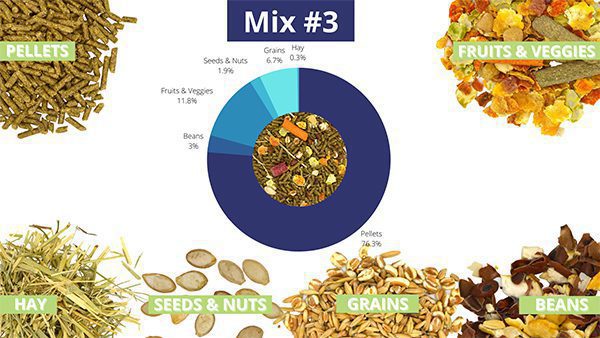

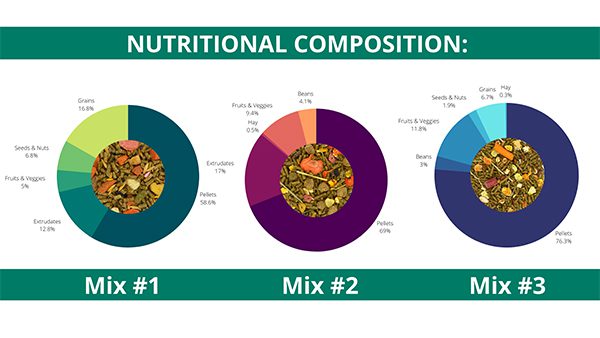

The following charts show all of the components included in each mix and what proportion of the bag they comprised.

Mix #1:

Mix #2:

Mix #3:

Notes on the Inclusion of Hay in Mix-Based Foods:

- As referenced earlier, our evaluation of foraging mixes incorporating hay revealed inclusions at less than 1% of the entire bag.

- Additionally, these pieces of hay fail to deliver the desired effect of stimulating foraging as animals eventually become uninterested in the hay and still select for the softer extruded pieces and grains.3

- Nutritionally, the inclusion of this small amount of short, choppy hay provides no significant benefit to a pet’s dental or gastrointestinal health and does not replace any amount of the free choice loose grass hay you should offer. To this point, the “foraging” claim on these mixes is nothing more than marketing as nutritional and enrichment impact or benefit is nonexistent.

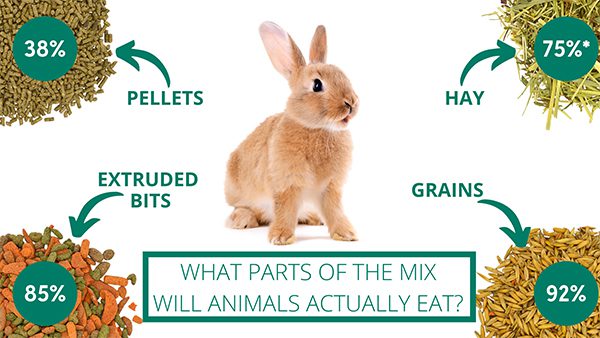

Which Ingredients are Likely to be Eaten?

The following charts show the nutrient composition of three popular mixes, compared to what small pets are likely to selectively consume. To calculate what animals would selectively eat, published research data was referenced which showed that pet rabbits consumed an average of 38% of pellets, 85% of extruded bits, 92% of grains, and 75% of hay in a mix.5

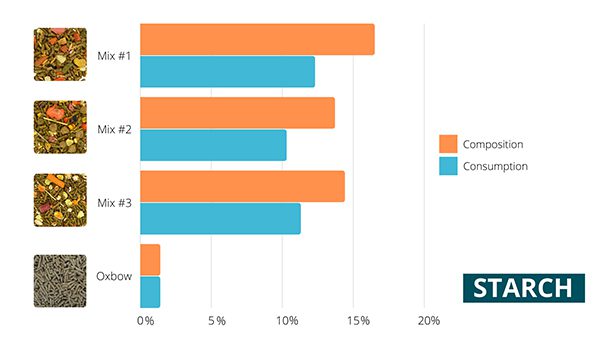

Nutritional Imbalances: A Look at Fiber and Starch

In analyzing the composition of popular mix-based diets, it is clear to see these products are nutritionally imbalanced for small herbivores. Obvious nutritional imbalances include:

- Inadequate Fiber

- Excessive Starch

- Inadequate Protein

- Inadequate Calcium: Phosphorus Ratio

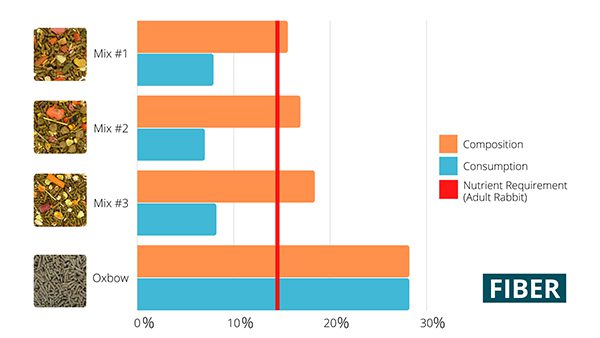

Fiber

Published recommendations for fiber in the diet of an adult rabbit is minimally 14% and typically the lower the starch, the better for gut health.15,16

On top of this, there are other potential negative attributes commonly seen in muesli mixes such as synthetic flavors, colors, and preservatives.

Understanding documented small mammal consumption patterns and what an animal is likely to consume from the mix, the issue of inadequate fiber is exacerbated, mainly stemming from selection against the pellet portion of the diet in favor of sugary fruits and starchy vegetables (most commonly peas, carrots, and corn).

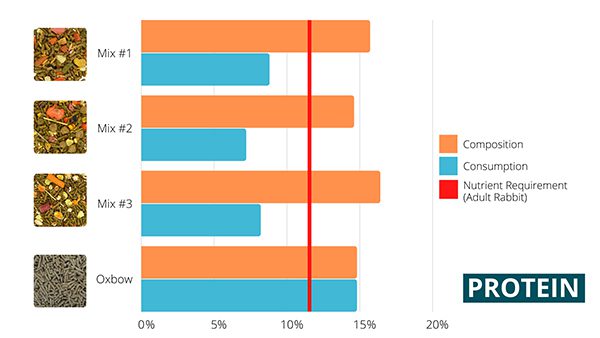

Protein

Furthermore, minimum protein requirement for adult rabbits is recommended to be 12% which is not fulfilled by intake of any of the three mixes.15,16

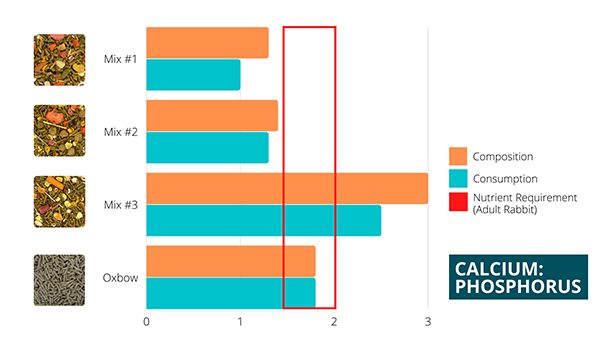

Calcium: Phosphorus Ratio

Lastly, a balanced calcium to phosphorus intake is vital for bone and tooth health maintenance, with recommended ratios between 1.5:1 and 2:1.16,17

Again, consumption of all mixes fell outside of this recommendation.

The Sticky Truth about Starch

As we know, these animals are hard-wired to selectively feed which will lead to unnecessary starch replacing critical fiber in the diet.

- This inevitably leads to a greater likelihood of digestive health issues due to inadequate fiber which is the leading cause of gastrointestinal disturbance in rabbits.18,19

- Diarrhea, GI stasis, obesity, and dental issues have all been linked to low fiber intake.17

- Additionally, low fiber paired with high starch diets can result in disruptions to the microbiome (dysbiosis) leading to loose stools and bacterial overgrowth that can become life-threatening.20

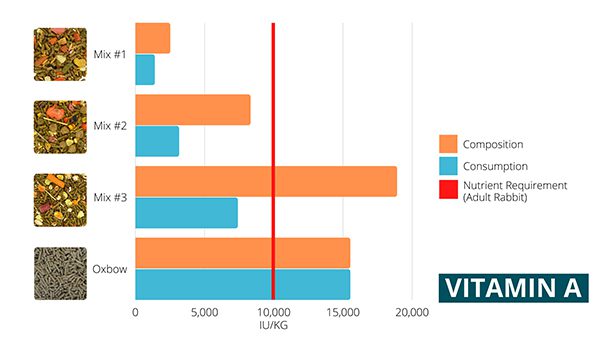

Vitamins & Minerals

In addition to inappropriate levels of other key nutrients, our data show that selective feeding patterns may be leaving nutritional gaps in required vitamins because micronutrients are typically added to pellets that are selected against.1

For our purposes, vitamin A was used as a measure of micronutrient addition and inclusion. Adult rabbits have a recommended intake of at least 10,000 IU/kg of the diet.16 Using rabbits’ natural and documented feeding patterns, none of the analyzed mixes will meet this nutrient requirement.

Because one of the primary purposes of pellets/commercial diets is to fulfill micronutrient (vitamins and minerals) requirements, this can lead to significant health problems. With guinea pigs, in particular, inadequate vitamin C intake resulting from selection against pellets (which contain the added vitamins and minerals) can be detrimental if not supplied elsewhere in the diet.

True or False: Mixes are perfectly adequate for my small pet and will support their health and well-being.

FALSE: Despite what manufacturers may lead you to believe, many popular mixes (including the three we analyzed) present real, potentially serious threats to your pet’s health and well-being. Areas of health that can be negatively affected by mixes include:

Digestive Health

The low fiber and high starch concentrations in mixes, when coupled to the concentrate selective feeding behavior of small animals, have serious implications for digestive health in small mammals, including the risk of GI stasis and potentially life-threatening changes to the microbiome.17,20

Dental Health

Mixes have also been directly correlated to an increased likelihood of dental issues in rabbits. In surveys and assessments of pet rabbits, the most commonly documented issue was dental disease which was directly linked to animals fed a muesli mix.3 Furthermore, scientific studies evaluating the adequacy of mixes have specifically noted radiographic changes in rabbits that are indicative of early dental disease.5

One study directly assessing dental health found that rabbits fed muesli mixes, even if hay is offered, had more tooth curvature and longer cheek teeth, both signs of early dental pathology, and 37.5% of rabbits fed only a muesli mix developed evidence of dental disease over the 17-month study.4

The research and data are very clear; muesli mixes dramatically increase the likelihood of rabbits and likely other small mammals with open-rooted dentition (constantly growing teeth) developing dental disease, which is one of the most severe and difficult to treat diseases in exotic companion mammals.

References

- Harcourt-Brown, F.M. 1996. Calcium deficiency, diet and dental disease in pet rabbits. Veterinary Record 139.23: 567-571.

- Lebas, F., P. Coudert, H. De Rochambeau, and R.G. Thébault. 1997. The Rabbit – Husbandry, Health and Production (2d edition) FAO publ., Rome, pg. 223.

- Mullan, S.M., and D.C.J. Main. 2006. Survey of the husbandry, health and welfare of 102 pet rabbits. Veterinary Record 159.4: 103-109.

- Meredith, A.L., J.L. Prebble, and D.J. Shaw. 2015. Impact of diet on incisor growth and attrition and the development of dental disease in pet rabbits. Journal of Small Animal Practice 56.6: 377-382.

- Prebble, J.L., and A.L. Meredith. 2014. Food and water intake and selective feeding in rabbits on four feeding regimes. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 98.5: 991-1000.

- Jekl, V., and S. Redrobe. 2013. Rabbit dental disease and calcium metabolism–the science behind divided opinions. Journal of Small Animal Practice 54.9: 481-490.

- Prebble, J.L., F.M. Langford, D.J. Shaw, and A.L. Meredith. 2015. The effect of four different feeding regimes on rabbit behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 169: 86-92.

- Miller, G.R. 1968. Evidence for selective feeding on fertilized plots by red grouse, hares, and rabbits. The Journal of Wildlife Management: 849-853.

- Somers, N., B. D’Haese, B. Bossuyt, L. Lens, and M. Hoffmann. 2008. Food quality affects diet preference of rabbits: experimental evidence. Belgian Journal of Zoology 138.2: 170-176.

- Gidenne, T., F. Lebas, and L. Fortun-Lamothe. 2010. Feeding behaviour of rabbits. In: Nutrition of the Rabbit, Eds: de Blas, C. and Wiseman, J. CAB International. Pgs: 254-274.

- Mykytowycz, R., 1958. Continuous observations of the activity of the wild rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus (L.), during 24-hour periods. C.S.I.R.O. Wildl. Res.

- Myers, K., and W.E. Poole. 1961. A study of the biology of the wild rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus (L.), in confined populations II. The effects of season and population increase on behaviour. C.S.I.R.O. Wildl. Res. 6, 1–41.

- Gibb, J.A. 1993. Sociality, time and space in a sparse population of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Journal of Zoology 229.4: 581-607.

- Franz, R., M. Kreuzer, J. Hummel, J.M. Hatt and M. Clauss. 2011. Intake, selection, digesta retention, digestion and gut fill of two coprophageous species, rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus), on a hay‐only diet. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 95.5: 564-570.

- National Research Council (NRC). 1977. Nutrient Requirements of Rabbits: Second Revised Edition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF), 2013: Nutritional Guidelines for Feeding Pet Rabbits. FEDIAF, Brussels (Belgium).

- Lowe, J.A. 2010. Pet Rabbit Feeding and Nutrition. In C. de Blas and J. Wiseman (eds.) Nutrition of the Rabbit 2nd ed.). CAB International. Pp. 294-313.

- Gidenne, T. 2003. Fibres in rabbit feeding for digestive troubles prevention: respective role of low-digested and digestible fibre. Livestock Production Science 81.2-3: 105-117.

- Rees Davies, R. and J.A.E. Rees Davies. 2003. Rabbit gastrointestinal physiology. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 6.1: 139-153.

- DeCubellis, J, and J. Graham. 2013. Gastrointestinal disease in guinea pigs and rabbits. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 16.2.: 421-435.

- Melillo, A. 2007. Rabbit clinical pathology. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 16.3: 135-145.

- Clauss, M., B. Burger, A. Liesegang, F. Del Chicca, M. Kaufmann-Bart, B. Riond, M. Hassig, and J.M. Hatt. 2012. Influence of diet on calcium metabolism, tissue calcification and urinary sludge in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 96.5: 798-807.

- Tschudin, A., M. Clauss, D. Codron, A. Liesegang, and J.M. Hatt. 2011. Water intake in domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) from open dishes and nipple drinkers under different water and feeding regimes. Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 95.4: 499-511.